As I wrote last week, the anti-ESG pushbacks are playing out differently across the Environmental, Social, and Governance pillars. For the Environmental and Social pillars, legislation and litigation seem to lead, respectively. For Governance, proxy resolutions are the preferred method. Of course, each has a mix of pushback strategies.

ESG proxy resolutions, a significant trend in the corporate landscape, have been well-supported over the past few years. They have garnered anywhere from 25-33% support, and in some cases, even getting majority support, as seen with Jack-in-the-Box. This proxy resolution was focused on the basics of carbon emissions, with the final backing reaching an impressive 57%. In another case, Key Bank proactively conducted a racial equity audit, avoiding the need for a vote.

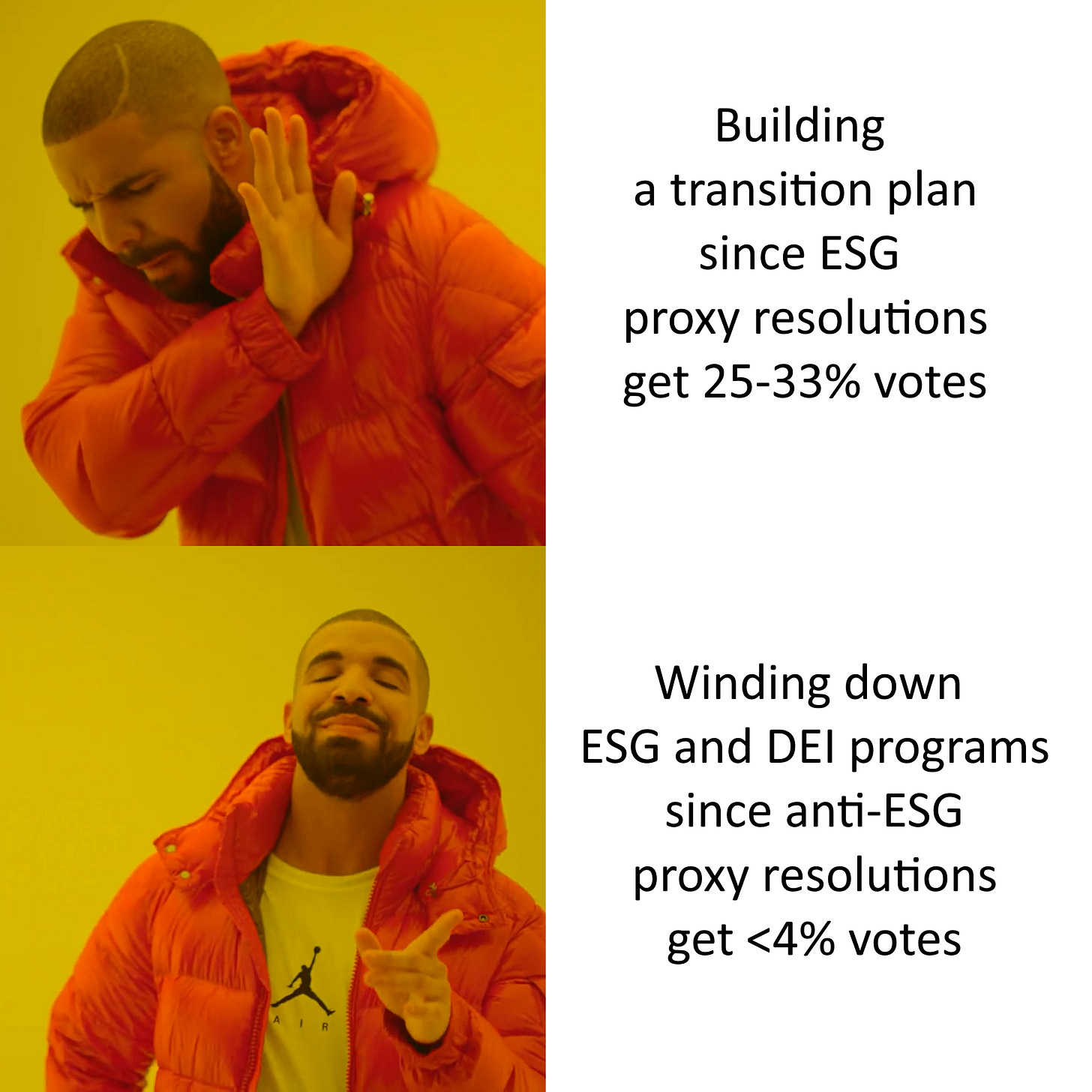

On the other hand, the Anti-ESG crowd is attempting a similar tactic, but their efforts are met with a significantly lower level of support, averaging an abysmal 4% or less.

Despite the higher level of support for ESG resolutions, greenhushing is rampant, and companies are pulling back on the term ‘ESG.’ Even the WSJ has turned its back on ESG for the latest politically charged term, ‘woke,’ in “Anti-Woke’ Shareholders Are Going After Corporate Boards.”

And so, we can turn to Drake to explain what is happening with the anti-ESG push.

Or, as another meme expression goes:

Companies would wind down ESG programs with minimal pushback

rather than listen to stakeholders and attempt to transition.

C'est la vie, I suppose.

However, the uptick in activist investors on both sides is an essential trend for companies to pay attention to. Companies seem to favor the anti-ESG pushback due to reputational risks from stakeholders (think cancel culture) rather than what investors seek. This is a governance misstep, as reputational risk management is more nuanced than management teams may realize and has only a short-term effect (depending on the issue).

Part of the management team’s attention to the anti-ESG may be because the short term is often the focus, despite some thought-leaders proclaiming that the board and management team’s role is the long term. Reality doesn’t match that idea, and this should be no surprise.

In 2020, Reuters estimated the hold for US equities was only 5.5 months. In 2023, an eToro survey also found that the holding period significantly dropped over time and was now nine months, steadily coming down from a holding period of five years in the 1970s.

And so, it is a lonely place to be either an activist shareholder or an investor focused on the long-term. So, what can an investor do against the tide of the anti-ESG and this short-term perspective?

Well, it starts with ownership, as I hear time and again.

Engagement is often preferred over divestment, as investors seize the chance to change and improve the company rather than just letting it run without considering its risks, opportunities, or impact. This involves short-term trade-offs, including capital projects, in pursuit of resilience. While ownership affords opportunities for this engagement, there are three things needed for this to be successful:

A receptive and open management team

An understanding of the trade-offs and recognition of their role in long-term sustainable growth and resilience

Other like-minded investors who recognize the transition opportunity and are long-term focused and will vote their shares on related proxy resolutions accordingly

The first is needed for direct engagement and advising. The second is the reality that needs to be overcome, as inertia is perhaps the most powerful force in business. The last bullet creates pressure where direct engagement is not working.

All of these are the benefits of investor ownership. Over the past year, there’s been rising attention on proxy resolutions at the intersection of Governance involving corporate performance, long-term, and the management team.

One of the most high-profile examples of attempting to drive change (or challenge a board) through ownership and pressure was when California and one of the world’s largest fossil fuel companies were involved.

In January of 2024, Exxon Mobil sued its shareholders (Arjuna Capital) after they brought up an Environmental-related proxy resolution. CalPERS, the largest public pension fund in the US, decided to vote out the entire Exxon Mobil board in the next AGM. In its letter about the decision, it articulates the point of ownership:

When you own shares of stock in a publicly traded company, you have a vested interest in how that company is run and whether its leaders are doing all they can to ensure lasting financial success.

You have a right to have your concerns heard by corporate directors and executives. They work for you.

CalPERS further called out the threat explicitly:

If successful, the legal action could diminish the role—and the rights—of every investor in improving a company’s bottom line.

While the stand was made, on average, 95.2% of votes favored the board. Again, inertia is a powerful force.

Now, keep in mind that CalPERS has not been investing in tobacco companies since 2001.

In another case, just last week, we saw a mighty campaign favoring a $46B pay package for Elon Musk, Tesla's CEO. This was approved with 72% of the votes (and is a bit more complicated for legal reasons) as the stock is down 28% this year, and car sales are sluggish. The company’s reincorporation from Delaware to Texas was also approved (again, that legal issue).

In another example on the other side, earlier this year, there was a proxy contest at Disney involving investor Nelson Peltz. Peltz, unhappy with the current board and Bob Iger’s leadership, was fighting for two board seats, even though Disney stock was up in the months leading up to the AGM. Peltz failed to secure enough votes in the fight by a considerable margin. Ultimately, Peltz decided to sell his stake (and release influence) in Disney.

Whether the stock is down, as in the case of Tesla, or up, as in the case of Disney, investors seem little swayed by disruptive board proxy resolutions. The results of this AGM season may have some investors, even some of the largest investors in the world, wondering what the value of ownership could be when change is so difficult. I realize these statements here are oversimplifications (discounting dual-class shares, proxy advising services, and institutional investment firms), but they do bring up a good point.

Just like a company can’t address a systemic E, S, or G issue without the support of an ecosystem, activist investors looking to drive systemic company change and lasting financial success can’t do so without the support of other investors.

Returning to where we started, divestment isn’t an option, as boards let the anti-ESG and status quo lead the charge. One potential solution is the movement of the ‘big three’ asset managers (State Street, Vanguard, and BlackRock) and their new proxy choice programs, which are currently rolling out. This will pass some of the voting control from the investment firm to the owners more directly.

Proxy choice can’t be all that activist and ESG investors rely on. While engagement from investor to company is critical for change, engagement across the investment ecosystem is also needed.

In 2021, we famously saw Engine No. 1, with only .02% of the votes, convince the big three to vote their way and place two out of three board candidates at Exxon Mobil. While this was supposed to be a wake-up call for boards, it hardly has been. The engagement campaign is worth examining for its material intersection and persuasiveness.

A friend of mine, Andrea Bonime-Blanc, has said, “The time of being inactive on a board is over.” So, is this statement perhaps true: “The time of being an inactive investor is over?”

Again, there are network effects to consider, and it appears to be a matter of how far you will go to bring others to your side. If you are voting along an ESG risk (not a non-material risk) and change doesn’t come, divestment might be the only option left.