Recently, I had a conversation with someone in Financial Services about various topics, and we inevitably landed on the ESG pushback and the confusion between sustainability and ESG.

He told me a story where he was talking with a financial analyst who revealed that when there is a material intersection between an ESG topic and the business, it can protect returns and manage risk more effectively.

My friend responded, “Well, as a financial analyst, when would you ever consider something that isn’t material?”

Right!

I’ll admit that some investors prefer values-based impact and actively seek those funds, but material risks and opportunities are at the core of the functional transition that so many crave while aligning with what the business can influence or direct.

Yet, the concepts around ESG are not well understood, as we are constantly reminded of the climate trouble we’re in and ongoing systemic racial and gender concerns. As a result, companies try to address systemic issues without effectively considering three things: materiality, externalities, and trade-offs.

So, let’s have a little fun. Let’s examine an interesting thought experiment that can help us think about these three ESG concepts because as some call for its end again, they do it before companies understand it.

An ESG spin on the trolley problem

Have you ever heard of the trolley problem? It’s a dark ethical thought experiment that has become a popular meme lately. I will keep it high level, as this is an ESG newsletter, not a philosophical or psychological self-examination.

The problem goes something like this:

You are standing near a switch, watching a trolley coming down the tracks. The trolley is heading towards five people and will kill them all unless you throw the switch, diverting the trolley to a track where only one person is killed.

This problem reminds me of Spock’s death in Star Trek 2: The Wrath of Khan. In the movie, Spock sacrifices himself to save the Enterprise, saying that “the needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few.” In the trolley problem, there is no self-sacrifice, yet the statement’s sentiment becomes the ethical question at hand. Should you pull the lever?

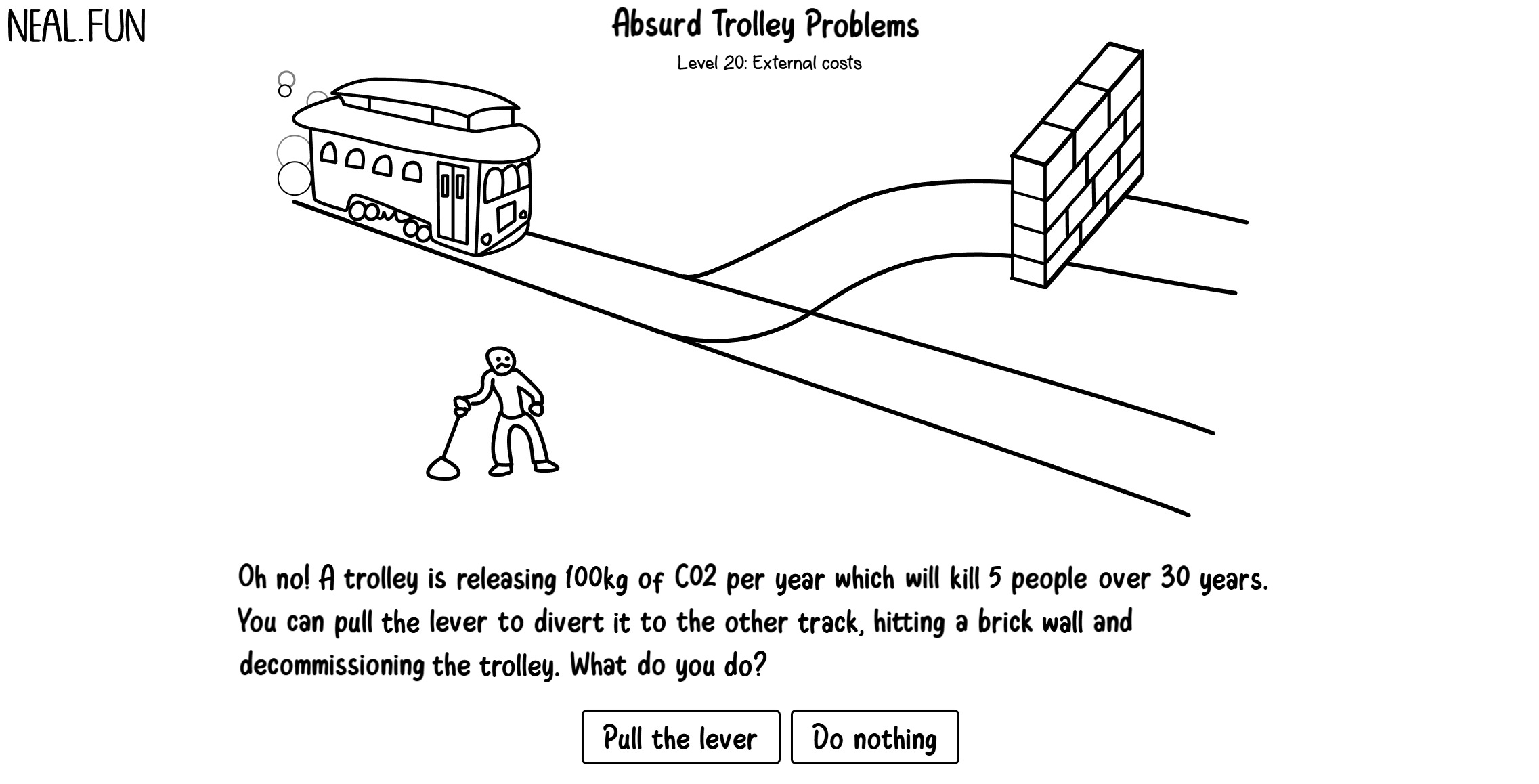

My oldest is obsessed with philosophical problems like this, and she came across a website full of thought exercises and interesting visualizations that challenge our perceptions (neal.fun). One of the games is ‘Absurd Trolley Problems,’ geared to judge if you can ‘win philosophy’ by saving as many lives as possible. It includes showing you a percentage of how many people agree with your choice.

One by one, we talked through the logic of each choice until we came to this one.

OK, so I did not pull the lever, and ESG concepts are the reason. As you can see below, most people disagreed with me, and I’m assuming you might, too.

Let’s look closer to see why I didn’t pull the lever.

Externalities and the trade-off

Considering the limited information we have here, externalities are at the crux of this scenario. Neal.fun recognizes this by naming the problem ‘External Costs.’

I describe externalities in ESG Mindset like this:

Externalities impact another party as part of the company’s operations and can be negative or positive, but often refer to the negative due to growing attention and accountabilities to ESG issues.

The externality in this trolley problem is pollution, which will cause the death of five people over 30 years. There is also a trade-off to consider. A trade-off is the consequence of the action taken and can reveal multiple sides. Here, the trade-off is saving five lives over saving a piece of machinery. In a binary choice with no other considerations, I might decommission the trolley and save those five people, but let’s weigh the externality and trade-off against other considerations, including materiality.

After all, this is a thought exercise.

Opening the scope with materiality considerations

In the problem, the trolley releases 100kg of carbon annually, which is .1 metric tons. Per the US EPA, one passenger vehicle emits 4.6 metric tons annually. By the logic of the trolley problem, one passenger vehicle would kill 50,000 people over 30 years. I assume a city would favor a low-carbon trolley over multiple passenger cars serving the same purpose.

While the carbon math is ridiculous, let’s treat it seriously as it illustrates some interesting points.

With relevant context and a little more information, we should ask if carbon is the most material consideration for a trolley car against the trade-off of keeping passenger vehicles off the road, especially if we’re trying to save lives from pollution. Perhaps this is an argument for the New York City Congestion Tax!

For a city or country that would be funding public transportation like trolleys, carbon is undoubtedly a material concern. In 2019, pollution in South Africa from coal and fossil fuels, including in vehicles, was the second-leading cause of death. Decommissioning a trolley would result in more passenger cars, resulting in higher pollution and more deaths over time, not to mention contributing to ongoing health issues that linger, reducing productivity and taking people out of the workforce. Not to mention that people leave cities due to poor air quality.

There is also a risk of litigation, as we are witnessing the rise in lawsuits against polluters for related health and social issues. A city (or individual, in this case) that decommissioned the trolley, causing increased pollution from other sources, could be sued for the resulting health issues at scale. Litigation can lead to reputational risks, which could lower tourism in the city.

A city might also consider that the trolley impacts economic mobility in low-income communities by providing safe and reliable transportation. This is not only a positive social externality but a material one. On the social side, the trade-off expands around those five people if the trolley carts ten workers on a regular schedule, and those workers now have jobs with healthcare. How many lives could be saved with those benefits? On the material side, those workers come into the city and spend money, generating income for local businesses, resulting in tax revenue.

Public transportation has many other benefits, including citizen access to all kinds of services, less need for parking structures, and more space for inviting public parks and tourist areas. For a city, increased tourism represents another material opportunity for increased tax revenue with environmental and social benefits.

For a company with an office in the city, the trolley represents a way to find a broader geographical base of talent who can come in and work, a material concern. Of course, remote work affords that, too. I’m not driving to Microsoft’s 11 Times Square office when I come to New York City! I take the bus or the train in.

Weighing material issues against the externalities and trade-offs gives us additional insights. Of course, there could be unknown considerations to account for, as well. One of those five people could be a life-saving ER doctor, or the trolley might be responsible for pedestrian accidents. Regarding the trolley, public safety is likely a more material issue than its carbon emissions.

Recognizing the issue with a limited scope (five people die over 30 years) is different than examining the issue with a wider aperture and additional data to discover that there may or may not be better or worse outcomes.

What the trolley problem shows us about our current crises

Today, I suspect more companies than not use externalities and trade-offs to support a binary choice rather than researching material risks and opportunities and coming to a thoughtful plan of action. Companies accept the externalities, proceed with ‘business as usual,’ and do nothing.

In a constantly changing world, constancy is a fallacy. Companies must do something, but it may not be as binary as pulling the lever and shocking the business with limited information.

Nuance is entirely lost. This is why I struggle with activists who want to turn off fossil fuels immediately and tough-to-abate sectors who refuse to change. Both groups are myopic on externalities, and neither is willing to concede ground. For activists, it is ‘pull the lever and turn off fossil fuels today.’ For high-emitting companies, it is ‘just keeping drilling.’

The current positive impacts, like access to energy that runs schools and hospitals, new construction, and economic opportunity for millions, become the argument for doing nothing against the trade-off of shutting dirty energy down. The negative externality continues unabated under the status quo, and we all suffer as climate change worsens. We must use the trade-offs to expand our understanding of the issue, not to support reasons for inaction.

After all, in the short-sighted cycle of financial reporting, the biggest trade-off may be to fund an action in the first place.

Materiality also plays a critical role here as the means to drive company progress, as I continually argue. Every company can only impact ESG risks and opportunities as they can, not through one myopic focus (I’m looking at you, carbon).

Progress happens in the messy middle over time. It considers externalities as one factor influencing a change, intersects with the materiality of the company’s operations, industry, and value chain, and leverages insights about the trade-offs to build a plan to responsibly transition.

Companies and financial services firms should make an informed choice, but it isn’t binary. Choose to plan, build, adapt, and transition as only your company can.

Today, the trolley is coming down the track and getting closer, but we have time to plan an additional switch and rail that moves the trolley out of the way entirely.

While it might seem like some of this analysis might lead to paralysis, we need to examine the data while recognizing that the trolley gets closer every day as an additional data point. Before too long, you have to act with the best information you have.

The one constant here is that the trolley progresses, even if your company doesn’t.

So, clearly understand the problem, externalities, materiality, and the trade-offs to get moving! If you don’t, there will come a time when the trolley is past the switch, and you can do nothing.

Take it from me: I solved philosophy at the end of this absurd problem! While the number could have been 51, I still think I made the right call.

In the case of the pollution risk, what gives you the right to throw the lever? We have democratic governance to decide this.